Interview with Pete Lockett–a world percussionist

Award winning musician, Pete Lockett, is one of the most versatile and prolific percussionists in the World. His percussive skills range from traditional Carnatic and Hindustani music of North and South India to traditional Japanese taiko drumming; from blues, funk and rock to classical, folk and ethnic and from Arabic to Electronic.

His boundless talents have earned him a reputation as one of the most wanted percussionists in the world. Pete has recorded and/or performed with Björk, Peter Gabriel, Robert Plant, Bill Bruford, Jeff Beck, David Torn, Vikku Vinayakram, Ustad Zakir Hussain, The Verve, Steve Smith, John Spencer Blues Explosion, Texas, Trans-Global Underground, Nelly Furtado, Phil Manzanera, David Arnold, Evelyn Glennie, Jon Hassell, Lee Scratch Perry, Primal Scream, Damien Rice, Jarvis Cocker, Craig Armstrong, Nicko McBrain (Iron Maiden), , David Mcalmont, Natasha / Daniel Bedingfield, U Shrinivas, Ronan Keating, Nitin Sawhney, Afro Celt Sound System, Vanessa-Mae, Errol Brown, Rory Gallagher, Simon Phillips, Pet Shop Boys, Beth Orton, Hari Haran, Kodo, Amy Winehouse, Mel C, A R Rahman, Eumir Deodato, Julian Lloyd Webber, BBC concert orchestra, Reshma, Sinead O’Conner and many more!

Pete arranged and recorded all the ethnic percussion for the last five 007 ‘Bond’ films and many other Hollywood blockbusters. He has also recorded in the Indian film industry, most recently in Chennai with AR Rahman on the blockbuster, SIVAJI, (Rajini Kanth).

Pete Lockett has a number of collaborative projects which are regularly touring: Projects include Kingdom of Rhythm, with Indian master drummer Bickram Ghosh, Taalisman with guitarist, Amit Chatterjee, Parallax Beat Brothers, Taiko to Tabla and Network of Sparks featuring Bill Bruford. He has performed to packed houses all over the world including Turkey, Australia, New Zealand, America, Canada, Malaysia, Thailand, Falklands, Argentina, Europe and India. He has released twelve CD’s with various projects under his own name.

Pete has taught and lectured Worldwide, including The Royal College and The Royal Academy of Music in London.

Technique articles in drum magazines number over a hundred and include MODERN DRUMMER’ in the US, DRUMMER MAGAZINE and RHYTHM in the UK as well as magazines in South Africa, Australia, Italy and Poland. Pete’s book, ‘Indian rhythms for the drum set’ (Hudson) is the first book of its kind covering Indian rhythms on the instrument.

Technique articles in drum magazines number over a hundred and include MODERN DRUMMER’ in the US, DRUMMER MAGAZINE and RHYTHM in the UK as well as magazines in South Africa, Australia, Italy and Poland. Pete’s book, ‘Indian rhythms for the drum set’ (Hudson) is the first book of its kind covering Indian rhythms on the instrument.

Pete was voted #1 BEST LIVE PERCUSSIONIST 2005 in a readers poll of Rhythm magazine.

We had an email interview with Pete.

Q1. Tell us something about how you got attracted towards music and what made you pick drums as your instruments? I mean any particular liking for drums?

It was a bizarre thing; I was just walking past a drum shop and I thought: I’ll have a drum lesson, for no readily explainable reason. I went in and it made sense to me in a way that other things in my life hadn’t before, you know, education or anything like that. I was aged 19 and was soon a drummer in a punk rock band. Similarly, my decision to transform from punk rock kit player to Tabla dude was totally unexpected. I was playing in a punk band on the London rock scene, and I accidentally stumbled across an Indian gig. It was Ustad Zakir Hussain and Ali Akbar Khan, and it was amazing. I didn’t know what they were doing. When you see Tabla for the first time, a good player, it’s the most amazing thing; it’s stunning. I had no concept of what he was doing, but that made an impact on me. Later, I saw Tabla lessons advertised in the local adult education magazine, and I was down there like a shot. Of course, the actual transformation took somewhat longer, many years of dedicated study, in fact.

Q2. Going for the variety of drums that you play, which one of them you like most and why?

My instrument is ‘Multi-Percussion’. However, I would say that certainly the Indian stuff is the most challenging, both intellectually and physically. To make a sound on the drums is very hard in the beginning and the rhythmic systems are very complex. It takes years to even get a foothold. However, an important area to master is your philosophy of what you’re doing and why you’re doing it, primarily. I want to be able to use what I can do effectively, and for me, to get more technically-able isn’t the only answer to making music. In fact, if anything, I want my playing to be less technical, I want less technique than I’ve got.

This attitude came from another sudden flash of inspiration. One of the turning points for me was listening to an album by Keith Jarrett called Spirits. He played it all himself, he did everything: Tablas, shakers, piano, guitar, saxophone, flutes, everything. I first got the album because it had Tablas on it; you know, closed mind: Wow, Keith Jarrett playing Tablas; I’m going to get into that! And of course, I got it home, and in my opinion at that time it was rubbish, so I just gave it away. About eighteen months later someone bought me the same record for Christmas, and it was incredible—it made such an impact on me, an impact that totally changed how I see music. If you listen to it, he’s playing Tablas with mallets and stuff, but what he’s doing is following the contours of the music and making great music on the Tablas with an unorthodox approach. And it made me realize that you can make music on an instrument without having any technique. Of course you’ve got to be of a musical mind, like Keith Jarrett. But it made me think, well, maybe I’m not on the right path here merely chasing technique.

Q3. Your connection with India has been for long. How you found Indian music enriching your own repertoire?

I feel incredibly grateful to have gotten involved in the Indian music world. It has given me so much knowledge, so many experiences and inspirations in our global musical village. I think we’re moving in a direction where music is not bifurcated into North and South Indian rhythms, east and west. Music breaks barriers within society and religions and people. You know, we musicians are all like brothers together, we make music together and we respect each other. It’s a model platform for development in the future and hopefully cross cultural collaborations will become more and more common.

Q4. While collaborating with artists world-over and playing different genres of music, how you maintain the rhythm and creativity of your own?

The creative process is the most important part of the thing for me. You can strip away technique and leave only the creative process and you will be left with a statement. That does not work the other way around. You will be left with a robot! One way to really get to the heart of that creative process is to work with people outside of the avenues you are comfortable working in. All the formalities and habits are stripped away and you have to start over. You have to rethink everything you do if you are going to get anywhere musically in these situations. In the absence of too many opportunities like this being available then I started to put together projects, tour and record. Why not put Bill Bruford together with an African drummer, Classical percussionist, Indian Dhol drum troupe and a craze British hybrid percussionist!! It has led to many interesting and positively challenging collaborations with so many amazing drummers and musicians. Whatever may be the style of musician, there is always a way to find common ground.

Q5. Which one offers more experimentation and improvisation—recording in a studio or playing live before the audience?

Luckily, I have enough coming in to be able to turn down stuff I don’t want to do. It gives me the freedom to focus on exactly what I want to do and not get sidetracked with other stuff. This also includes my schedules, so if I have been away a lot, I just schedule in studio stuff for a month. I record mostly at home in my own studio, so this also gives important time to my wife and home life. It is really important to not neglect these things and limit how much time you are away. It also gives me the license to balance studio work with live work. Ten times out of ten live works is the spiritual life blood of the musician, me included. You get the direct feedback from the audience and can really get absorbed in the moment. With studio work, it can be a little more analytical. Everything is to a click nowadays which is fine but leads to a more considered approach to every single note.

Q6. What, in your eyes, is the value of rhythm for human psychology? Do you feel percussion music has an impact on the psyche of humans?

I can only speak for myself and the answer for me is certainly YES!!! However, I am not some sort of ‘hum-drum’ pseudo psychologist who reads more into things than there actually is. If one has a creative output in any area, then I think that person is on a higher plain to achieve happiness. It is a personal fulfillment thing and it is an urge we all have, whether we exercise it or not.

I can only speak for myself and the answer for me is certainly YES!!! However, I am not some sort of ‘hum-drum’ pseudo psychologist who reads more into things than there actually is. If one has a creative output in any area, then I think that person is on a higher plain to achieve happiness. It is a personal fulfillment thing and it is an urge we all have, whether we exercise it or not.

Q7. How has been the journey as a musician so far? What else, if not drums, you would have chosen?

The only thing I could have been would be a comedian!! Definitely, not a politician. I have no idea who or even ‘what’ I would be without music. Thank goodness it found me!!!

Q8. What other passions you enjoy apart from music?

I love a bit of cooking. I do all the cooking at home. Also I love mucking about with photoshop and video editing on the computer, a bit of football on the tele and a good film at home with the wife and a bottle of red wine!

Q 9. Any advice or suggestion for young and budding drummers or our readers.

There’s getting good as a player, or accomplished, shall we say, and there’s becoming a player who’s in work; and they’re completely different areas. To get good technically necessitates, a little bit of obsession somewhere along the line. It’s difficult because you don’t want to be obsessive all your life, but to use the psychologists’ parlance, you’ve got to have some drivers in there to put the work in, to get it down.

The other important thing is to work out what you want to do. If you’re a family man, if you like being at home, you’re probably better off choosing to go the session route than ending up on a world tour for nine months. I think that’s something you should think about early on; otherwise you can have a disparate angle, and once you get into one of those areas, work builds up along that line.

So think about whether you want to be a recording player or a touring player, or whether in fact you want to be writing. Drummers don’t always think about that, and quite often they get a bum deal; they won’t be getting writing royalties and they might not be getting that much money. And if they’re a drummer in a band, that’s really big for a short while, they then get the disadvantage of being labeled as the drummer from X, which may not be any good for their future career prospects. So, I think it’s important for people to really consider what they want to do.

Q10. We would like you to speak a little about your book titled “Indian Rhythms For Drumset”. What is your target with that?

The book came about over a long period of time as I’d been trying to apply the Indian knowledge to the drum set and it took me many years to do that, to find ways of articulating those rhythms onto the drum set. Slowly, it came about through other percussion instruments as everything become ‘one’ and stopped being separate instruments in my mind and I began to think of them as a family of instruments which is why I call myself a multi-percussionist.

I was teaching the South Indian rhythmic system and that became the core of the book. Once I had my approach to the system in place I was able to approach the system in a slightly more abstract way so that the building blocks could be utilized by all musicians. I give people the building blocks and would then move on to whole compositions. I got a lot of positive feedback from students using this method. They could understand and perceive the building blocks and then see how they were built into the larger compositions and themes.

The next logical step was to articulate it onto the drums. Really, the book gives you two things, there is the system that can be for everyone and then there is the application for the drum set. The book contains the South Indian syllables / building blocks and the rhythmic structures and then the applications for anybody to use. I wanted to model the book on the book that covered African drumming on the drum set where the first big chunk is the history, the drums, the idiomatic setting and then the extrapolations on the drum set. I believe it is a book that will last a long time and is not a moment of fashion that won’t be of interest in five years. The whole development of the book came from the education method so it is kind of organic in that way. It never started out to be a book, but it ended up being one!

Q11. Can you tell me about your latest solo release, About Time?

I just finished recording my new solo album ‘About time’ which will be due for release mid 2010. Much of what I do live is densely layered unison stuff so I wanted to do an album of purely acoustic solos on individual instruments in lots of different time signatures. A lot of the rhythm constructs are ‘Indian’ inspired and weave around a simple accompanying bell or shaker pattern. It is now available online on iTunes etc.

Album Review—Inner Sanctum

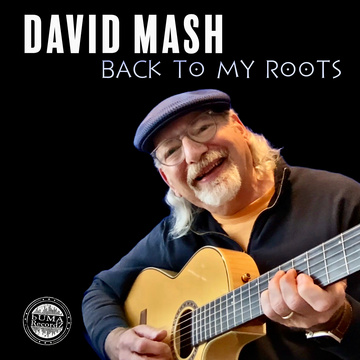

Album Review—Inner Sanctum  Album review—Back To My Roots

Album review—Back To My Roots  Album Review—Days of Gypsy Nights

Album Review—Days of Gypsy Nights  Album Review—Open by Stephen Wallack

Album Review—Open by Stephen Wallack